Nymi promises a future free of keys, PINs, and passwords, like a universal remote for modern life that uses your heartbeat like a fingerprint.

That’s the claim at least.

So what is this thing exactly? From the main page, we learn that Nymi is (1) a wristworn device that (2) uniquely identifies you from your heartbeat, (3) is capable of gesture recognition to (4) control various “smart” technologies. Most of that’s pretty standard fare these days, but #2 caught my attention. Is that even possible? An informal poll of friends and colleagues turned up a great deal of skepticism.

It took considerably more digging to find a more technical description on the website of the parent company:

I’m going to digress, but I can’t help myself – the mention of a gyroscope got me thinking about power consumption and battery life. While a typical MEMS accelerometer (e.g. the STMicro’s LIS2DM) can sip 10 µA while sampling at 100 Hz, the equivalent 3-axis gyroscope (e.g. ST’s L3G4200DT) gulps 6 mA. The device would need a 72 mAh battery to survive just 12 hours with the gyro alone, which, given their form factor, suggests either they measure rotation only rarely or the following claim in the FAQ page is nonsense:

I’m going to digress, but I can’t help myself – the mention of a gyroscope got me thinking about power consumption and battery life. While a typical MEMS accelerometer (e.g. the STMicro’s LIS2DM) can sip 10 µA while sampling at 100 Hz, the equivalent 3-axis gyroscope (e.g. ST’s L3G4200DT) gulps 6 mA. The device would need a 72 mAh battery to survive just 12 hours with the gyro alone, which, given their form factor, suggests either they measure rotation only rarely or the following claim in the FAQ page is nonsense:

But this is just nitpicking – devices can perform gesture recognition using an accelerometer alone. What about some of the bigger claims? Is it really possible to identify a person from their heartbeat?

But this is just nitpicking – devices can perform gesture recognition using an accelerometer alone. What about some of the bigger claims? Is it really possible to identify a person from their heartbeat?

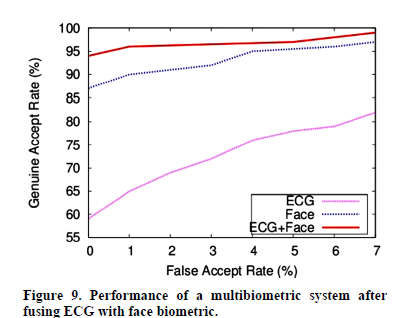

Although they promise a white paper some day in the future, Nymi currently provides zero data on the sensitivity or specificity of their algorithm. However, a couple of academic papers on the subject provide some guidance. One from 2004 showed that features extracted from an ECG could uniquely identify individuals independent of sensor location and subject anxiety. Another paper from 2012 demonstrated an algorithm with a nominal 10% error rate when using ECG data alone:

The pink curve plots general acceptance rate vs false acceptance rate for ECG data alone. The other two curves incorporate other biometric data to improve performance, which is not something Nymi claims to do. From Singh & Singh, “Evaluation of Electrocardiogram for Biometric Autherization” Journal of Information Security, 2012, 3, 39-48

Interesting! My doubts was misguided – the physical position, size, and condition of the heart varies enough from person to person to produce measurably different signals. Moreover, unlike some other biometrics, the presence of a heartbeat is pretty good evidence that the user is a real, living person, skirting a common problem for fingerprint and facial recognition technologies.

But a 10% error rate sounds abysmal, doesn’t it? Authentication – convincing yourself that a user is who they claim to be – is a fundamental problem in data security, so how does this compare to other implementations?

Robust systems demand multiple forms of identification, ideally in different media. This is why your bank ATM requires a physical key (a debit card) and shared secret (a PIN) and results in an error rate very close to zero. Nymi too requires a physical key (the band), but isn’t a 10% error rate equivalent to a 1 digit PIN?

Well, yes and no. Car keys have no authentication layer and your credit card has only a rarely checked signature, so any form of authentication would be an improvement. Even for ATMs, since people select their own codes and humans are awfully predictable, the distribution of 4 digit PINs is far from uniform. If you guessed the PIN 1234, you would be correct a staggering 11% of the time, and subsequently guessing 1111, 0000, and 1212 would improve your success rate to 20%. (I have no data to support this, but I’ll conjecture that the probabilities are significantly higher for a card found on the street – the people most likely to lose a card are also the people most likely to pick an easy to remember PIN.)

Nymi: Better than some idiot’s combination for their luggage

So while Nymi provides weaker security in the best case, this ECG thing might be a plausible “good enough” solution for consumer applications. Of course, I’m giving them the benefit of the doubt that their algorithm is comparable to the one described, that the device works reliably in the real world, and that the rest of the ecosystem is secure. Since Nymi does not provide any more detailed information or hands-on demonstrations, those assumptions are impossible to evaluate.

Looks like I’m stuck teasing this guy for using an absurdly inconvenient gesture to open the trunk of his Tesla.

What problem does this solve? I still need a free hand.

Which brings me to this product’s biggest issue: Even if the system is secure, what good is it? Nymi might unlock my smartphone or computer (tasks I don’t find particularly burdensome), but I struggle to think of anything else I might use it for. Maybe that’s my fault for not owning a Tesla, but there’s also no guarantee it will interact with any future piece of technology I might want it to. The damn thing isn’t even a watch.

But those aren’t technical shortcomings.

They should get together with the Angel guy and make one wristband thingy to rule them all! Unlock things but if you can’t be cause your heart rate has changed, detect an impending heart attack? Neither of these make sense so maybe they should combine forces and make one thing that also doesn’t make much sense.

It’s not just a 10% error rate, it’s a 10% false ACCEPT rate. This is the device signalling the requester that the user is person A when the user is actually person B. Errors usually show up as false REJECTs, which is when the device simply says that the user is not actually represented in the test population, despite a successful enrollment. A FRR of 10% might be tolerable, I think that might be the FRR for the fingerprint sensor on the HTC One Max phone; at least, that’s what all the negative press might lead one to believe. A FAR of 10% means that if a stranger tries to authenticate with the device, he’ll succeed in about 1 out of 10 attempts. Either the thresholds need adjustment, or the technology isn’t ready.